Casey Farm

Casey Farm

Stewards of the Land

Many people value Casey Farm for its timeless appearance. Moving through the farm today and with a bit more information, it is possible to absorb the thousands of years of cultivation and presence of the Indigenous Narragansett people. You can read the landscape features like stone walls and cleared fields to appreciate the tremendous labor that went into creating and maintaining them by people over the centuries—enslaved people, farm hands, tenant farmers, and agricultural professionals alike. The living and changing fields and gardens were planned for decades of changing needs by residents, owners, volunteers, and employees.

Learn more about all these types of people, get a window into the past, and find out how we are still planning for the future of this land.

"We Dwell Here"

performed by Lorén M. Spears, Executive Director, Tomaquag MuseumThe Casey Family

and their ties to the landMorey to Coggeshall to Casey

Remarkably, this land was owned by the same family for 253 years. In 1702, Joseph Morey acquired the three hundred acres on Boston Neck in the Narragansett Country of the colony of Rhode Island. In 1652, the land had been acquired from Cogninaquand, the leader of the Narragansett people, and passed through investors’ hands until Morey’s family settled permanently and set up a successful plantation that traded produce via Newport. Joseph and Mary Morey’s only daughter, Mary, inherited the land with her husband, Daniel Coggeshall of Jamestown.

Their son, also named Daniel Coggeshall, married a woman also named Mary, Mary Wanton. By then, the family were members of the Society of Friends, or Quakers. Daniel and Mary raised eight children, and their daughter Abigail would continue to live on the land into the early nineteenth century with her husband, Silas Casey. He was a merchant who made his living by shipping dry goods up and down the East coast, to the West Indies, and to Europe. Abigail, who was the mother of their ten children, was also descended from Quakers on both sides of her family. Silas descended from three generations of Irish immigrants who settled in nearby East Greenwich where Silas continued to own property along with managing the plantation they called Boston Neck Farm.

Boston Neck Farm

Boston Neck, named for the home city of its colonial purchasers, is a strip of land about seven miles long between the Narrow (or Pettaquamscutt) River and the West Passage of Narragansett Bay facing the island of Jamestown. First prized by Europeans as grazing land and a source of graphite, it became the perfect spot to produce goods like wool and cheese to ship overseas chiefly to the West Indies through the nearby major shipping city of Newport. In this “Narragansett Country” were many such plantations, of which Casey Farm was on the small side at three hundred acres; the largest ones were three thousand acres. Today, Casey Farm is the only intact plot left.

The family made a prosperous living until Newport was occupied by the British in 1775 when the whole area was plunged into an economic depression. After the Revolutionary War the farm’s owner was Silas and Abigail’s oldest son, Wanton Casey, who became a business partner with Silas. He had spent some time overseas in France learning the trans-Atlantic trade and time in the new territory of Ohio where he met his future wife, Elizabeth Goodale. Returning to the farm on Boston Neck in 1786 – 1787, Wanton and Elizabeth found that the international market was dried up and they decided to rent to tenant farmers. This became the pattern for the next two hundred years.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the economy improved with people discovering the desirability of coastal Rhode Island as a resort area to escape the heat of summer in cities like New York. Again, Newport was the pinnacle of this trend, but Casey Farm’s neighborhood now named Saunderstown benefited from a boatyard just South of the farm, which evolved into a ferry service, and then the Saunders House Hotel.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the economy improved with people discovering the desirability of coastal Rhode Island as a resort area to escape the heat of summer in cities like New York. Again, Newport was the pinnacle of this trend, but Casey Farm’s neighborhood now named Saunderstown benefited from a boatyard just South of the farm, which evolved into a ferry service, and then the Saunders House Hotel.

In 1842, the farm passed to the next generation owner, Thomas Goodale Casey, a New York resident who, with his relatives, spent summers at the farm. He took an interest in improving the farm, and, having gone to considerable difficulty to keep the three hundred acres together, Thomas Goodale Casey thought he was passing the property down whole to his nephew, Thomas Lincoln Casey. Unfortunately, Rhode Island did not recognize his New York will and property disputes continued until Thomas Lincoln Casey finally bought out or convinced relatives to give him sole ownership by the 1870s.

Washington Monument and Naumaukut

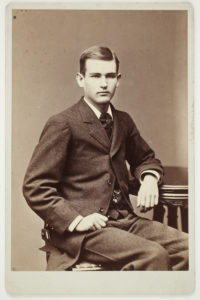

Thomas Lincoln Casey was the son of an Army general, Silas Casey. Thomas, too, served from the Civil War through the 1890s, and rose to the rank of brigadier general with his greatest accomplishment of engineering the completion of the Washington Monument. Having the head of the Army Corps of Engineers as the farm’s owner meant that the buildings were attended to with care, as were the family cemetery and the stone walls. He engineered a way to rehabilitate and flood the cranberry bog, finished the cow barn complex, and cared for all the outbuildings. The landscape included three apple orchards, one hundred elm trees, many acres for grazing sheep and cows, and a large woodlot. Thomas married Emma Weir, whom he met while attending West Point. Their sons who summered at the farm, Thomas Lincoln Casey, Jr., Harry Weir Casey, and Edward Pearce Casey, all followed in their father’s footsteps by studying engineering or architecture. The oldest and youngest sons stewarded the farm their father re-named Namaukut, making repairs and formalizing the piazza into a Classical porch.

Historic New England

Edward Pearce Casey, who attended l’Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris and practiced architecture in New York, married Lillian Berry. Having no children and no surviving immediate family members, they decided to donate the land, farm house, and outbuildings as a working farm entrusted to the organization started by their friend, William Sumner Appleton. The Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, as Historic New England was then called, took up the stewardship of the land in 1955.

Then and Now on the Farm

Thanks to Harry Weir Casey, we have windows into the past that we can compare with the exact same views today. Harry lived with his family in Washington, D.C., but spent each August and September on the farm his family had owned since 1702. A student at Yale Scientific School, Harry took up the relatively new hobby of glass plate photography to capture these images in 1878 and 1879. We replicated his photos in September 2020. You can enlarge each picture to see how much has changed and how much is still here today.

The land presently called Casey Farm was originally cultivated for organic agriculture by the native people of southern Rhode Island and has been farmed consistently for hundreds of years. Currently we grow crops from May through the end of fall for a Community Supported Agriculture program, an onsite farmers market, a local gleaning organization, and other local markets, always keeping in mind the land’s history and the importance of organic practices to the planet around us.

The land presently called Casey Farm was originally cultivated for organic agriculture by the native people of southern Rhode Island and has been farmed consistently for hundreds of years. Currently we grow crops from May through the end of fall for a Community Supported Agriculture program, an onsite farmers market, a local gleaning organization, and other local markets, always keeping in mind the land’s history and the importance of organic practices to the planet around us.

Since I began working this land in 2012, we have never used synthetic chemicals on the land and only use organic means to control unwanted pests. There is a strong ecosystem here because of these methods with many beneficial insects helping to balance the “pest” populations. We believe in being good stewards of the land and leaving it in better condition than we found it.

–Lindie Markovich, Farm Manager

Agriculture Today and Tomorrow

Casey Farm cultivates about ten acres of land to grow a large variety of organic vegetables, herbs, and flowers. We produce honey from beehives on site and eggs from our heritage breed chickens. The people who do the hard work of farming in this mercurial New England climate are a full-time farm manager, assistant farm manager, lead farmhand, up to four seasonal hired hands, and many workshares who earn part of the harvest by investing their labor.

Casey Farm cultivates about ten acres of land to grow a large variety of organic vegetables, herbs, and flowers. We produce honey from beehives on site and eggs from our heritage breed chickens. The people who do the hard work of farming in this mercurial New England climate are a full-time farm manager, assistant farm manager, lead farmhand, up to four seasonal hired hands, and many workshares who earn part of the harvest by investing their labor.

Through the mentorship and examples of our hard-working farm crew, we want to inspire others from a young age to see the benefits of being connected to the land and maybe even choose it as a career.

The two major ways that people get access to Casey Farm produce are at our seasonal farmers markets (held on Saturday mornings, mid-May through October) and through our Community Supported Agriculture Program.

Community Supported Agriculture

emphasis on communityCasey Farm began offering the first USDA-certified organic CSA shares in Rhode Island in 1994.  Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) members support the farm by purchasing a share of fresh fruits, vegetables, herbs and flowers to be picked up each week here at Casey Farm. They throw in their lot with the farm, paying ahead of time and taking home their part of the harvest weekly, whatever that may be. These days, the fortunate members generally receive a greater value than they paid into the program, plus many other benefits.

Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) members support the farm by purchasing a share of fresh fruits, vegetables, herbs and flowers to be picked up each week here at Casey Farm. They throw in their lot with the farm, paying ahead of time and taking home their part of the harvest weekly, whatever that may be. These days, the fortunate members generally receive a greater value than they paid into the program, plus many other benefits.

Members can get to know their farmers and share recipes, and pick-your-own crops provide the opportunity to get into the fields and see how your food is grown. CSA members also receive a household-level membership to Historic New England.

Shares typically feed up to four people. The summer CSA runs for twenty weeks from June through October. Shares vary each week, but here are some examples of what members can expect throughout the season:

Spring – salad greens, snap peas, strawberries, root crops

Summer – tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, blueberries

Fall – cooking greens, sweet potatoes, garlic, winter squash, apples

Please contact the farm office or visit our website for more information and to sign up.

Slavery in Rhode Island

The Casey Farm we appreciate today was built on the labor of enslaved people. While we have no direct evidence that enslaved people worked at Casey Farm, we do have evidence that Silas Casey (1734-1814) was an enslaver of at least three people named Wat, Ezekiel, and Moses who may have worked here and/or at his other property in East Greenwich, Rhode Island. We know that generations of the Morey/Coggeshall/Casey family directly enslaved at least fourteen people at their properties. They lived in a culture that condoned and promoted slavery and benefited from an economy based on the labor of enslaved people, that we in many ways have inherited.

By 1755 during the heyday of the plantation culture in Southern Rhode Island, called the Narragansett Country, the percentage of enslaved people was far higher than any other Northern colony. Scholar Christy Clark-Pujara of the University of Madison-Wisconsin sheds much light on the subject in her book Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island.

All northern colonists, New Englanders in particular, participated in the West Indian and Atlantic slave trades, but Rhode Islanders were the most deeply entrenched. Their domination of the North American trade in African slaves gave them increased access to slaves. Merchants and tradesmen in Newport and Providence put their slaves to work in their homes and shops and on their ships. Farmers in the Narragansett Country put thousands of enslaved men, women, and children to work producing foodstuffs and raising livestock for the West Indian trade. Local slave labor played a key role in the growth of commerce in Rhode Island; moreover, abundant plantations of the West Indies provided farmers and merchants with a near-perpetual market for their slave-produced goods. (page 29)

Professor Clark-Pujara points out that enslaved people “lived and labored in Rhode Island from the birth of the colony, in 1636, until slavery was abolished in 1842.” We are dedicated to keep researching and bringing facts to light about all the people whose lives contributed to making this place. A more complete exploration of the history of slavery in Rhode Island and at Casey Farm can be found on our partner’s website, the Rhode Island Slave History Medallion project: https://rishm.org/washington-county/north-kingstown/casey-farm/.

People Who Worked the Land

From what we know about this farm and ones like it when it was founded in the first decades of the eighteenth century, a variety of crops were grown relying on the labor of enslaved Indigenous and African people. Professor Christy Clark-Pujara in her book Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island described what is also evident in the archives for Casey Farm:

Located along the southeastern coast of Rhode Island, the Narragansett Country—also known as South County—was first cleared and farmed by Native Americans. The region’s rich soil, moderate temperatures, and easy access to Newport trade made it an ideal place for large-scale commercial agriculture and grazing. There was no staple crop. Instead farmers bred horses, cattle, and sheep, manufactured dairy products (primarily cheese), and cultivated small amounts of Indian corn, rye, hemp, flax, and tobacco. Slave labor was essential to the economy in the Narragansett, as slaves produced nearly all the exported goods. (page 26)

Although the 1790 census for the state indicates there was a small number of enslaved people residing in Rhode Island, the presence of many of Silas Casey’s laborers are listed separately in the census under the column of “other free persons,” suggests that he was no longer a slaveholder.

Tenant Farmers and Hired Hands

It is documented that Casey Farm was mainly worked by tenants, some African American, some Native American, some of European descent, throughout its history. In addition, Silas Casey’s records show payments to twenty-seven men (nine of whom were identified as people of color) working as hired hands. These farmers produced corn, wheat, rye, barley, apples, raised sheep, dairy cows, and made famous Narragansett cheese.

It is documented that Casey Farm was mainly worked by tenants, some African American, some Native American, some of European descent, throughout its history. In addition, Silas Casey’s records show payments to twenty-seven men (nine of whom were identified as people of color) working as hired hands. These farmers produced corn, wheat, rye, barley, apples, raised sheep, dairy cows, and made famous Narragansett cheese.

One person of color that appears often in the account books over a span of fifteen years is Cuff Gardner. He did a variety of work on the farm, from killing hogs and butchering, to carting wood, setting apple trees and trimming the orchard, and building the orchard wall. He was paid in cash as well as salt, corn, and potatoes. Prof. Clark-Pujara gives us insight into life in Rhode Island as a free person of color like Cuff Gardner:

The vast majority of black and mixed-race Rhode Islanders…were free by the turn of the nineteenth century; however, free was a terribly relative term. People of color still had to contend with slavery on multiple levels. The practice of slavery still continued, as did statuatory slavery. Free blacks also had to cope with the legacies of slavery—most urgently the poverty that came with nothing but freedom. Moreover, being free did not mean having rights. Free blacks had ambiguous legal protections because they were not universally recognized as citizens…Interracial marriages were banned in 1789, and African American men were barred from voting in 1822. (page 94)

In 1804 Silas Casey noted Cuff’s “lost days,” which included “Negro Election” and “Negro Town Meeting,” and a half day lost to being unwell. By reading deeper, we see glimpses of personal time and social life, particularly the regular participation in Negro Election festivities.

Silas Casey entered into agreements with two men of color who worked as tenant farmers: Henry Niles (whom Casey identifies as a Native American) and Henry Carr (a free African American). Both men lived in a small house about a half mile from the main farm house rent-free in return for working for Casey a specific number of days per week. A display about the lives of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Carr as interpreted through archaeology is in the Casey Farm House Museum Gallery.

Stewards of the Land Over Time

A summary of those who lived, worked, and/or owned the land now known as Casey FarmFor 10,000 years, humans have occupied the land on which Casey Farm now sits. The land was called Namcook by the Narragansett people, indigenous to this land. By the end of the 1650s, the land was sold and renamed “Boston Neck.” From 1658 onward, this farmland was owned and occupied by tenant and gentleman farmers until 1955 when Historic New England, then known as the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, took ownership.

These are the names of former owners and occupants of Casey Farm.

| 10,000 years before present Indigenous people, the Narragansett, called the area Namcook |

1658 Atherton Company Purchase and renamed area Boston Neck. Owner Amos Richardson |

1675-1702 Changed hands with owners named James Brown, John Payne, John Richardson, Timothy Clarke, George and Elliner Havens, and John and Mehitable Dexter |

1702 James Morey, owner, and Mary (Wilbor) Morey, the first ancestors of the Caseys. (1st generation) |

1705 Mary Wilbur (Morey) Coggeshall and Daniel Coggeshall, Sr. (2nd generation) |

| 1724 Daniel Coggeshall, Esq., owner, and Mary Wanton Coggeshall, built the farm house circa 1750 (3rd generation) |

1784 Silas Casey and Abigail Coggeshall Casey (4th generation) |

1786-7 Wanton Casey and Elizabeth Goodale Casey, son and daughter-in-law of owners |

1814 Wanton Casey, owner, and Elizabeth Goodale Casey – (5th generation.) |

1842 Thomas Goodale Casey (6th generation) |

| 1855 Thomas Lincoln Casey and Emma Weir Casey (7th generation) |

1896-1925 Thomas Lincoln Casey, Jr. (8th generation) |

1896-55 Edward Pearce Casey and Lillian Berry Casey (8th generation) |

1955-Present SPNEA, now called Historic New England |

These are people who were tenant farmers and renters of Casey Farm, unless their roles are otherwise stated.

| 1699 Cornelius Hightman | 1702 Mr. Batty |

1716 William Smith |

1724 Thomas Willett | 1771 Ackers Sisson | 1772 William Ellery |

1775-83 Mortgaged 195 ¾ acres to Benjamin Gardiner | 1782-3 William Browning | 1784 James Owens | 1785-6 Reynolds Knowles, Daniel Coggeshall, and James Owens |

| 1802-3 Henry Niles, rent of small house and farm laborer | 1804-8 Henry Carr, rent of small house and farm laborer | 1809-10 Langworthy Pierce, Henry Carr | 1811-20 Francis Carpenter and George W. Watson | 1812 James Pone, rent of small house | 1811-14 George W. Watson | 1814-21 John L. Watson |

1820 Jeremiah N. Potter | 1822-35 Vincent Gardiner | 1840-56 Benjamin Hazard |

| 1857-66 John H. Caswell | 1867-88 Thomas J. and Sarah H. Gould

daughters |

1888-c. 1919 Robert W. Watson |

1924-65 Archie Rose | 1965-67 Frederick Seymour, resident caretaker | 1968-88 Mr. and Mrs. Archie MacLaughlin, resident caretakers |

1988-92 Mary Elizabeth MacLaughlin and Casey MacLaughlin, resident caretakers |

1993-2006 Mike Hutchison and Polly Williams, resident farm managers | 2006-10 Patrick McNiff, resident farm manager | 2010-14 Ashley Cordt, resident farm manager |

2014 to present – Lindie Markovich, farm manager